- Home

- Amy Peterson

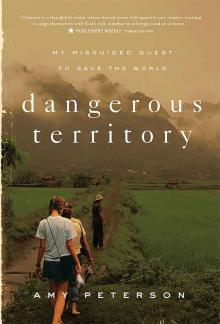

Dangerous Territory Page 9

Dangerous Territory Read online

Page 9

Apostleship confused me. The book explained that while the office of “apostle” had only been given to twelve—the original disciples minus Judas and plus Paul—the gift of apostleship was given to many. Apostleship was the gift of church planting, of leadership in “new works” of Christ.

But I was perplexed. If churches were supposed to be led by men, as I’d been taught my whole life, how could a woman have the gift of apostleship? Was it possible for me to preach the gospel to men? What was I supposed to do, start churches then put them on hold until a man could be found to preach? If Veronica was the beginning of a church in our town, what would we do when it grew?

The doctrines I’d grown up with—about gender divisions in church leadership—seemed to make even less sense outside the United States. What was a female missionary to do? She could preach the gospel in evangelism, but once a church was formed, she was forbidden from preaching in the church pulpit? She could teach men about the Scriptures in small groups or one on one (or could she?), but not as head pastor of a church? And wasn’t there something ethnocentric—even racist—in the American church’s willingness to send female missionaries to preach and teach in foreign countries while refusing to let women preach or teach white American men?

But even as I began to doubt the theology of gender I’d grown up with, it continued to exert a powerful influence over my thinking about marriage. Choosing to get married, I was certain, would mean sacrificing my dreams to follow my husband’s. I wasn’t sure if I wanted a career or if I wanted children, but I felt sure that choosing one meant giving up the other. And I was convinced that I needed to marry a man who was a leader. I could only imagine him like the church leaders I’d grown up with—someone who loved the spotlight, who entertained an audience, who had more Bible verses memorized than I did, who knew more theological answers.

As Charley and I walked through the mall in Chiang Mai, we passed a jewelry store. I tried to imagine what I’d say if he proposed that week. I tried to imagine saying yes. I thought maybe I would say yes.

* * *

Conference was heaven. We stayed in a mountain resort, and every morning we’d gather, hundreds of us, a crowd of people of all colors and ages, the on-fire and the burned-out, Methodists and Baptists, Mennonites and Pentecostals, Yankees and Texans, Hong Kongers and Canadians, shoulder to shoulder singing “In Christ Alone.” We listened to people teach from the Bible in our native language; we heard reports from teachers in every country of amazing things that had happened. We rested.

At dusk I’d sit with girls from my grad cohort in a gazebo, where we would read passages from Lauren Winner’s Mudhouse Sabbath out loud to each other. After dark we’d gather around laptop screens and watch indie films on DVD. In the afternoons Charley and I would walk around the resort and find a clandestine corner for a kiss.

One afternoon he helped me with a project. My parents’ church had asked me to record a message for a father-daughter Valentine’s dinner. Charley borrowed a video camera, and I put on my pink button-down, found a well-lit spot in front of a lush green hedge, and began. I hadn’t been given much instruction as to what the church wanted, so I decided to try to honor Dad by speaking of things he’d done right as a father. Each of my three points told a story about him, then used Scripture to show how his practice of fathering was in line with God’s design for dads. I drew on the small amount of Greek I knew from a class I’d taken in high school, the inductive Bible study skills I’d learned in college, and my natural gifting as a teacher. Telling stories and tying them to Scriptures, I exhorted the dads at the banquet to follow God’s design and my dad’s example.

When I finished, Charley turned off the camera, but didn’t say anything. “Was it okay?” I asked.

“Is that what they wanted?” he asked in response.

“I don’t know. It’s for the father-daughter banquet,” I answered, annoyed by his lack of enthusiasm.

“Yeah. You did fine, I guess,” he said.

We took the tape out, returned the video camera to its owner, and slipped the recording into an envelope to drop off at the post office when the conference was over.

Perhaps Charley saw something that I hadn’t. In attempting to honor my dad, I’d crafted a message that exhorted men, men who were older than I was. If I’d been thinking, maybe I would have written a message directed to the daughters. Instead, I’d told older white men what to do. I’d interpreted the Scriptures in a video that would be played in a conservative church in the south.

About a month later, the morning after the banquet, Dad called me. “How’d it go?” I asked enthusiastically.

“Not so well,” he said. “Some of the men walked out.” He paused. I was confused. Why did they walk out? Were some of the daughters wearing immodest dresses?

“They told me afterward that it wasn’t right for you to be teaching the men like you were.”

Silence deepened on the phone line, the eight thousand miles between our lives suddenly seeming more real than ever. Inside me, a door swung shut.

This church—not even a church I’d been a member of, not a church that financially supported me—had asked for a favor. I’d spent my free time and small missionary allowance to prepare and to mail the video. It had never occurred to me, when they asked me to record a message for the father-daughter banquet, that they wouldn’t actually want a message. It hadn’t occurred to me that they’d want me to craft a talk for a church event without using Scripture. It hadn’t occurred to me that my dad would hear that kind of response without offering a counter-argument. But he himself had been taken aback by their response.

Anyway, this whole discussion, this question about “women’s roles” in the church, was feeling increasingly irrelevant to me. The questions just didn’t make sense halfway around the world, for believers in fledgling churches in countries where faith in Christ was forbidden. I would need to study it all again, but my experience overseas was leading me to think that the churches of my youth were getting something wrong in the way they understood Paul’s instructions to Timothy, those comments about women being “silent” in the church.

I left the argument, tired of the words, hurt that my dad had to be the one to tell me what had happened. If the elders of that church really cared about me, they would have addressed it with me themselves, but they didn’t. I never heard a word from them.

I left the argument, and drove my motorbike out to the beach, walked in the sand with my students, and ate freshly caught fish. I saw where the Spirit was moving, and I followed, needing no one’s permission but God’s.

* * *

Maybe we broke up because of that, because Charley saw women as “helpers” and “followers,” men as “heads” and “leaders.” Maybe we broke up because I loved my life overseas and he didn’t love his. Maybe there were things about ourselves we hadn’t admitted to each other. Maybe there were a thousand reasons, not just one.

After conference, Charley and I traveled with a group of our friends to a beach in southern Thailand, and then he came to visit my country for a few days, staying in the spare apartment in our building on campus. I knew that having Charley stay on our floor on campus might signal to the conservative local culture that I was, after all, a promiscuous American, just as they’d assumed from what they knew of Americans on TV. But I didn’t care much about appearances—surely those who knew me would know better than to believe any gossip.

Charley ate with me at my favorite restaurant and came to dinner at Veronica’s house. I rode the train back to the capital with him, and we spent two days there at Camille’s before he caught his plane to China.

We talked to her about our relationship over dinner at the Australian burger joint, laid everything bare.

“It seems to me,” she said, looking thoughtfully at me, her eyes crinkled with questions, “that if you want to come back here next year more than you want to be with

him next year . . . that means something.”

It didn’t, though. I’d read numerous missionary biographies where people postponed marriage for years, refused proposals, and left their spouses, all in the name of evangelism. Love that overthrows life was Shakespeare (or maybe Shakespeare in Love), not Scripture. Certainly it was possible to love my work more than I loved my boyfriend, yet still love my boyfriend?

I turned her words, and my counter-arguments, over in my mind. Later, leaning against Charley on the blue sofa at Camille’s, I said what seemed inevitable to me—and must have been to him.

“We can’t keep doing this,” I spoke softly. “I love you, but I don’t want to marry you. We need to break up, for real this time.”

I thought about the first time I’d seen Charley, in an honors English class our freshman year. I hadn’t noticed his muscular calves or soft, full lips. I had noticed his shaggy hair and round nose, the way they reminded me of a brown bear cub. I’d noticed his wry smile and sarcastic wit. When in that Great Books class our text was Romans, he hadn’t brought a printout to class like most of the other students—he’d brought a worn, leather-bound MacArthur Study Bible. I’d set my Bible on the desk, too, a secret signal saying talk to me. Soon he had stopped sitting in the back row, and moved up to the front row to sit next to me.

Now, at my suggestion that we needed to break up, he didn’t argue. I think he’d known for a while how tenuous my love was. Maybe that’s what he’d been afraid of—afraid to tell me real things about his life in case I was just waiting for an excuse, a good reason to break it off. My love was a kind of waiting, testing love, always uncertain of whether he deserved it. His friends in college had warned him that he deserved better than that, better than me, and they were right. Love should be unconditional, but mine always had strings. It was always waiting to see if he would be good enough, good enough for me to give up everything else for.

I let him go.

Interlude

A Brief History of Women In Missions

Prior to about the 1820s, the word missionary was a male noun. There were missionaries, and there were missionaries’ wives (though in the 1800s, that was a new thing, too—most missionaries up until then had been celibate males). But for a woman to be a missionary was against “the whole tenor of Scripture” and “out(side) of her sphere of duty,” as a writer in Christian Lady’s Magazine claimed in 1836. In the early Victorian period, women were to stay at home; they were the weaker sex, they were prone to fainting fits. They were angels or whores, but nothing in between.

In Victorian England, Christian women who felt a calling to something other than wifehood and motherhood had few options. Increasingly, though, women who wanted to work in the public sphere found more freedom to do so if they married missionaries and moved across the ocean. Overseas, missionary wives could do jobs that at the time were considered inappropriate for women in England or America.

Ann Haseltine was one who sought “a life of usefulness” and first made the role of “missionary wife” a legitimate calling for nineteenth-century American women. At twenty-three, she married Adoniram Judson, and two weeks later, they set sail for India, then Burma. They studied the local language and saw their first convert. During the first Anglo-Burmese War, Adoniram was imprisoned on suspicion of being a spy. For seventeen months, Ann lobbied for his release, living in a shack outside the prison gates, nursing a baby, and writing tragic descriptions not of her own plight, but of the way Burmese females were treated: the infanticide of baby girls, young girls being given in marriage, status and human rights conferred on women only through their husbands.

After Adoniram’s release, they stayed in Burma. Ann wrote a catechism in Burmese, and translated the biblical books of Daniel and Jonah. In 1819, she translated the Gospel of Matthew into Thai, the first time any Protestant had performed Bible translation into that language.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, women like Ann Judson were self-deprecating in the letters they sent back home. To maintain Victorian norms of domesticity, they masked their participation in traditionally male enterprises. But increasingly, they were doing more than keeping house overseas. After Ann Judson’s death, Adoniram married twenty-eight-year-old widowed missionary Sarah Boardman, who was no shrinking violet. Sarah had chosen to stay in Burma after her first husband’s death, and had taken over his work, making evangelistic tours through remote jungles, preaching the gospel to the Karen people, and supervising mission schools.

Around the same time, Betsey Stockton became the first unmarried female missionary sent out from America. A freed domestic slave, she traveled with a missionary couple, partly to serve them and partly to do mission work. In the Sandwich Islands, now known as Hawaii, she started a school for fishermen, farmers, and craftsmen.

More and more women, single and married, became active as missionaries in their own right. By the mid-nineteenth century, the word missionary no longer referred only to celibate males. Women began telling their own stories, too. Memoirs of British Female Missionaries (1841), collected by Jemima Thompson, was a kind of manifesto promoting female missionary endeavor, opening with a long essay on “the importance of female agency in evangelizing pagan nations.”

Some men championed women on the mission field. Hudson Taylor welcomed single women to the China Inland Mission, sending them out two by two to the villages, praising their effective preaching. When Christian and Missionary Alliance members disagreed about women’s roles in ministry, their leader A. B. Simpson said, “Let the Lord manage the women. He can do it better than you, and you can turn your batteries against the common enemy.”

But sometimes women had to fight their agencies—and even their own husbands—to fulfill their callings. Lottie Moon, a Baptist missionary to China, saw more than a thousand people come to Christ as a result of her work. In early letters home, though, she wrote things like, “I halted at two villages and had an enjoyable time talking to the women. That the men chose to listen too was no fault of mine!” Later, she took a stronger stance: “What women want who come to China is free opportunity to do the largest possible work. . . . What women have a right to demand is perfect equality.”

Pearl Buck, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Good Earth, grew up as the child of missionary parents in China. As an adult, she wrote about watching her parents negotiate their roles, describing her mother’s realization that her husband, Andrew, did not believe in the priesthood of all believers, only in the priesthood of men. “What?” Buck wrote. “Was she not to go to God direct because she was born a woman? Was not her brain swifter, keener, clearer than the brains of most men? Why—was God like that, Andrew’s God? It was as though she had come bearing in her two hands her rich gifts of brain and body, giving them freely and as touchingly sure of appreciation as a child—and her gifts had been thrown back at her as useless.”

Women on the mission field made great strides, but still they struggled against patriarchal assumptions that undergirded some Christians’ beliefs. Then, in the twentieth century, many of the female mission societies that had formed over the previous hundred years merged with general denominational mission boards. When they did, women typically lost their positions of leadership.

* * *

Historically, women on the mission field changed the Christian view of women’s roles and women’s spheres. Over about two hundred years, the church’s position on women in ministry changed dramatically. Yet for many American Christians, a woman’s place on the mission field remains limited to supporting roles.

When I was overseas, my ministry experiences didn’t fit with the mixed messages I’d received about women in the church. My questions about the roles of women in missions multiplied.

What does it mean for a woman to be a missionary?

Can she be a nurse or a schoolteacher, but not a church planter?

Can she preach?

; Can she teach men, or only women?

Can she teach brown-skinned men, but not whites, as if brown-skinned men are somehow less of men?

Can she lead a co-ed Bible study?

Can she lead a church?

If a man asks her how to be saved, can she answer him?

If he’s never read the Bible, can she explain its meaning to him? Or should she say, “I’m sorry, I can’t talk to you about what the Scriptures mean. I’m a woman. If God loved you, he would have sent a man whom I could support in this work.”

The churches I grew up in wouldn’t necessarily have endorsed that last line, but they agreed with the message at the heart of it. Women were not to teach men.

Or, if they did allow women to be church planters and Bible teachers on the field, they had a reason: women can lead churches on the mission field but not back home because of the extreme need on the mission field. Women can do it, they’d say, but it’s “not God’s best.” They’d compare female missionaries to Deborah, whose good leadership of Israel they claimed was a “judgment” on Israel’s men for not assuming leadership themselves. She was made judge over Israel, they said, to shame the men for being so lacking.

The thing is, the book of Judges never indicates that God viewed Deborah’s leadership that way.

In the same way that female missionaries changed the church’s perspective on the role of women in ministry, my experience as a woman on the mission field began to change my mind. It was this experience that first nudged me toward understanding that both men and women could be called to all kinds of service for God. Observing an Asian church in its infancy showed me how the systems and structures that had developed over centuries in the West were less biblical, more man-made. Living in and understanding another culture helped me see that much of what I thought it meant to be “woman” was culturally prescribed, not essential. Much of what the church had taught me about womanhood had more to do with customs—Victorian customs—than with Scripture.

Dangerous Territory

Dangerous Territory