- Home

- Amy Peterson

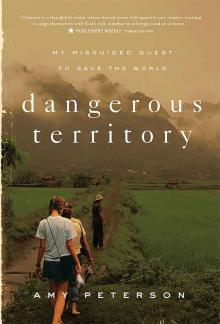

Dangerous Territory Page 10

Dangerous Territory Read online

Page 10

But women like Ann Judson, Betsey Stockton, Lottie Moon, and Amy Carmichael showed me another way. A woman’s vocation is her own, and not her husband’s. And that’s a truth that is always good for the church.

12

Further Out

Mission begins with a kind of explosion of joy. The news that the rejected and crucified Jesus is alive is something that cannot possibly be suppressed. It must be told. Who could be silent about such a fact?

Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society

Placing my red satchel on the flat wooden desk, I organized my textbooks inside it as the freshmen filed out of the classroom. Veronica remained seated at her desk at the side of the room, waiting for everyone to leave. Then she came up to me.

“When can we study the Bible again?” she asked. “I have to tell you something. I have a plan.”

I lifted my eyebrows. “Tonight?” I suggested.

That evening I made green tea and set some crackers on a plate. Veronica brought a tangle of rambutan, spiky-skinned pink fruits. I squeezed one until the skin broke, then peeled it and popped the translucent white flesh into my mouth, sucking and then spitting out the seed. Most of the food lay forgotten, though, as she began telling me the plan she’d devised while I was in Thailand.

“Amy,” she said, “I have a plan to change the minds of my people. I will begin by telling my friends and family about what I have learned, and then I will ask them what they think about it. I can show them the film that you showed me. And then,” she said, “they will tell their friends and family, and it will be like in that movie Pay It Forward—the good news will spread all over! What do you think?” she asked.

I had to smile, seeing that a girl who had never been instructed to share her faith was bubbling over with desire to do so. It was a beautiful plan. She proceeded to tell me that it was already in motion.

“I showed my family the Jesus movie while you were gone. My father was angry when he watched it, and said it was not true. But then he watched it again. And again. He watched it four times, and invited our neighbors to come watch it with him. My father and the neighbor agreed that the film wasn’t true.”

While the men seemed unconvinced, Veronica’s neighbor had said, “The people of our country don’t know about this story, and they need to. Can I make a copy of the movie?” Veronica told him that her teacher wouldn’t permit it—but he made a copy anyway. Then he took it to his ancestral village, and everyone came out to watch it.

Worry tinged my wonder at Veronica’s story. She needed to be more careful, but what could I say? The last time I’d warned her she’d quoted Scripture at me. Maybe my fear, not her zeal, was the real problem.

The following week, I went to dinner at Veronica’s house. I sat on a woven mat on the floor, knees together, feet tucked neatly behind me, as did Veronica, her parents and younger brother, and the neighbor who had watched the Jesus film. We served each other food from communal bowls. I liked this cultural tradition: we never served ourselves, only each other, always trying to honor someone else with the choicest pieces of meat, always tuned in to whose bowl was nearly empty and filling it with rice. At each meal, we took a bite of rice first, to respect the food that brought their ancestors through times of famine.

As we finished eating, Veronica began to translate for us. The adults wanted to talk about Jesus, but they began by saying what a sacrifice it was for me to come to their country. I protested—I loved their country and was happy to be there. It wasn’t a sacrifice.

“It is a sacrifice,” Veronica’s dad insisted. “The Holy Spirit must have led you here.”

“Yes,” I nodded, shocked by his casual mention of the Holy Spirit. “That’s true.”

“My neighbor says that he wants more details about the film,” Veronica translated. I agreed to get him a copy of the book of Luke in his own language.

“He says he’s not convinced that the film is true,” Veronica continued. I didn’t try to convince him, just nodded. Since they had already invoked the Holy Spirit, I figured I could, too.

“Maybe the reason you’re so interested in the film is that the Holy Spirit is calling you,” I suggested. Even I could understand his response: he nodded, saying basically, Yes, I think that’s true.

As the sun went down, Veronica gave me a ride home on the back of her motorbike. She came inside to pick up the book of Luke for her neighbor, and then hugged me good-bye. It would be so much easier, culturally, for her to keep following Jesus if her parents also came to faith. I prayed that they would.

Veronica and I continued studying the Bible together every Sunday night, and she regularly told her best friends, Sarah and Cecilia, what she had learned. Finally, they both decided that they wanted to study the Bible, too, so I began an introductory study with them on Monday nights. Sometimes all four of us would zip around town on their motorbikes, stopping to eat a favorite local snack: tiny pink shrimp, encased in a translucent gelatinous rice dumpling, topped with fresh herbs, chilies, and crispy fried onions. I grew to crave it.

Veronica would call me on the phone when she was reading the Bible. Once she called me after reading Romans 5. “Amy, this is so wonderful!” she said. “This letter—a letter of Paul, right?—has so many beautiful things. He really understood the gospel. I feel so wonderful! Sometimes I call my friends when I read something like this, but they never understand why I’m excited. I just had to call you.”

Another day, after she’d used a devotional she picked up at my apartment, Veronica called to tell me that the words of the prayers in the book expressed her feelings exactly. “And I don’t know if this is right or okay, Amy, but I feel that God is inside me and around me all the time. Is that okay?”

She’d read Mark, Luke, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians; large parts of Genesis, Exodus, the Psalms and Proverbs, and all of Ecclesiastes. Sometimes she copied out pages of Scriptures for her friends when they were worried or stressed. Her best friends from high school, who were attending universities in other cities, received letters filled with Scriptures. For an assignment in speech class, she was considering giving a speech about the gospel.

When Veronica began to vocally question the teacher of her government class, bringing her Bible to the classroom and reading it while the teacher lectured, I reprimanded her softly. She needed to be more careful. One night Veronica asked me why I hadn’t told any of the third-year students, who had much better English ability, about Jesus. I told her that I’d had spiritual conversations with some of them, but they hadn’t shown interest. Still, I felt vaguely guilty. Should I have been doing more?

But I was doing a lot. The second semester seemed to pass much more quickly than the first, my days crowded with teaching, tutoring, language lessons, Bible studies, and reading for my grad classes. Anxieties about my own identity—whether I wanted a career or marriage, what kind of adult I was going to be—dissipated once I’d made my decision to return to teach another year. I began to see myself living long-term in this country, so even though cultural differences sometimes irked me—the campus loudspeakers beginning their songs and announcements at 5:45 a.m., for example, or the English faculty fatalistically sure that no change in their teaching methodology would make any positive difference for the students, or the university assemblies where everyone in the audience chatted throughout the president’s speech—a sense of contentment, more than anxiety, began to characterize my days. Veronica had helped me understand my identity: I was a messenger, and a Bible teacher. Maybe that was enough for now.

I began exploring new parts of the town on my bike by myself, buying notebooks in a bookstore, trying a coffee shop—a real one, not a plastic stool on the hot sidewalk, but a place with normal sized tables and air-conditioning. But I wanted to go farther. I wanted an electric motorbike.

Our organization’s policy was that first-year teachers could not own motorbikes. But I

convinced Camille that an electric motorbike was a different category, something between “bike” and “motorbike,” and that since I had signed on to return for another year, I was almost a second-year teacher already. She smiled, and I went to the ATM to take out two hundred dollars.

Tina took me shopping the next day. I trusted her to be a fair cultural broker. She’d have to negotiate a good price for me as well as a good price for her friend who was selling. We settled on a maroon motorbike with space-age curves. It was practically a toy, only accelerating to 40 kilometers per hour (about 25 miles an hour), and the fully-charged battery would allow me to travel about 50 kilometers (30 miles) before I’d need to plug it in again.

In the parking lot of the shop, Tina laughed at me as I tried out the motorbike for the first time. I wore grey dress pants that a local tailor had made for me, and a button-down and cardigan. I wore Birkenstock sandals, totally culturally inappropriate (I should have been wearing pointy-toed flats or feminine sandals with heels), but I was never able to give up my footwear. I donned a helmet and awkwardly, in fits and starts, drove in circles, smiling like an idiot.

I bought the motorbike even though I didn’t have a place on campus to keep it. There was a storage room on the first floor of my building that would probably work, but the first floor was a few steps above ground level, and there was no ramp. I’d learned by now that if I requested a ramp to be built, I’d hear, “Yes, sure”—and then nothing would ever happen. But I figured if I bought the bike, the university might feel more compunction to follow through. Until then, I stored my purchase at Tina’s house. Since her dad was an administrator at the school, I hoped he might help push the project through any red tape.

Two weeks later, the ramp was built. Veronica gave me a ride to Tina’s home, a big house out in the country. I brought flowers for Tina’s parents, and we all sat in their front room, eating mangoes from their trees and drinking water. Tina translated for us, assuring her mother that the weather was indeed suitable for me here (even though I looked so thin), and assuring her father that she and Veronica would both follow me back to campus since it was already dark. I told Tina’s parents that they were taking care of me just like my own parents would—a way of thanking them without saying thank you. In this culture, to say thank you was rude: you only thanked people you didn’t have a relationship with. Instead of thanking friends, you simply acted reciprocally; they took you out for yogurt, then you took them out for yogurt. They watched your motorbike for you, and you brought them flowers.

Back on campus, we realized the ramp had been built in a corner without enough room to angle the motorbike onto it. Together, we managed to get the machine up, but I doubted I’d ever be able to do that on my own. I rolled my eyes at the world, and said good night to Tina. Veronica came upstairs with me.

“You seem too tired to study tonight,” she said. “Let me rub your shoulders.” We sat on the bed as she worked the tension out of my back. She told me about a book a Catholic friend had given her.

“The book says that Catholics care about history, tradition, and ceremony, and Protestants just follow the Bible. Is that right?” she asked.

“That’s probably a reasonable way of understanding the differences,” I agreed. Veronica said that the emphasis on ceremonies like confession didn’t seem to fit with what she’d read in Paul’s letters: he stated that in the past, people had to offer sacrifices, but since Jesus was the final sacrifice, we didn’t need to offer them anymore.

Sometimes I wondered if Veronica needed my help at all.

13

Deeper In

As you wend your way from village to village, you feel it is no idle fancy that the Master walks beside you.

Lottie Moon, May 10, 1879

My phone rang on the first day of April.

“Amy?” said Veronica. “I have to tell you something.” Something in her voice made me nervous.

“What is it?” I asked, worried. She paused.

“I have cancer of the liver,” she said finally, her voice sounding choked.

“What?” I couldn’t believe it. What kind of quack doctor had she seen? This couldn’t possibly be true. And if it were, we would find a way to get her the best care. Surely this wasn’t—

“April fools!” she cried.

Everything happened fast that month. One weekend I traveled with Sarah and Cecilia to Sarah’s home, in a coastal village a couple of hours from the university. We met up with her high school friends, walked down bright streets under umbrellas to shade our skin from the sun, went to the beach and played in the water in our clothes—no immodest swimsuits for us. Sarah’s mother cooked for us, roasting small birds over an open fire in the yard. I ate them, feeling tiny bones crunch in my mouth, and I ate the clams and fried green vegetables, too. But I didn’t try the stomach of the chicken or the heart of the pig. Sarah, Cecilia, and I slept spooned on a small wooden platform in one of the three rooms in the house. I woke around three to the noise of her mother preparing foods to sell in the market that morning, and went outside to pee in a hole in the ground.

A few weeks later, Veronica traveled to the capital with me for Easter, a holiday that most people in the country had no idea existed. At Camille’s house, we met two dozen other locals on Saturday night to watch Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ. I felt uncomfortable, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on why. Didn’t we all already know the story of the crucifixion? Watching this movie felt like we were emotionally manipulating ourselves. I found myself glad that it was just a poor quality DVD, with badly translated dialogue dubbed in, playing on a small screen.

As the story progressed, Veronica found me.

“I’m not sure I can watch this,” she said.

“You don’t have to,” I agreed. “We can go into the other room.” Instead, she sat in the back, sometimes averting her eyes from the screen, sometimes writing in her notebook instead of watching the film. She remained removed, at some level, from all the interactions that day, as if she was watching and testing the people there, waiting to ascertain how trustworthy they were. I wanted her to have Christian friends from her own culture, but I also recognized that this was just Veronica: always a bit of an outsider, analytical and passionate, hesitant to be a joiner.

Over dinner, though I couldn’t understand the words, I watched her argue about the Bible with a boy who’d watched the film with us. Her eyes flashed, and I couldn’t tell if she was excited or angry. Later Veronica told me that the boy knew of a house church just fifteen kilometers, about nine miles, from our university.

“Are you going to go?” I asked.

She laughed. “Are you really asking me that?” She glowed.

The next day, she attended a local church for the first time, later meeting a group of people in a public park for games, songs, and lunch.

Back in our city, we met for our weekly study. Veronica told me she had finished reading the whole New Testament, and that her friend Anna, whom I’d never met, had just finished reading the book of Luke. Anna told Veronica that, after reading, she believed in God and Jesus, but she wasn’t sure if she wanted to be a Christian. Veronica planned to continue studying the Bible with her.

The very next weekend, Veronica, Sarah, and Cecilia traveled back up north for a retreat planned by one of the local Christians Veronica had met at Easter. I rode the train with them, the four of us giggly, excited, and nervous to be traveling by ourselves. I wondered what their parents thought; the girls said their parents understood where they were going, and were okay with it. Not having enough language ability to communicate with their parents myself, I had to trust that that was true.

The retreat would be led entirely by indigenous Christians, mostly Philip, a twentysomething with a passion every bit as strong as Veronica’s. Ten of them met in the capital and took another bus into the mountains, leaving us foreigners behind. I r

elaxed at Camille’s house, reading her novels, going shopping for DVDs, working on my graduate school assignments. Camille took me to a jewelry store where I bought a necklace with the shape of our country dangling in silver from a chain, and we met with a small group of teachers to talk about what was happening in my city and how it might inform our work in other cities.

Finally, the girls returned. I met them at the train station so we could get back in time for school the next morning.

“Sarah and Cecilia are Christians now!” Veronica announced almost as soon as I saw them. I hugged the girls and murmured how happy I was for them. “We were all baptized,” she added. Though flustered and pleased, I found myself immediately wondering if Sarah and Cecilia had felt pressured to do something they weren’t ready to do. I wished they would have talked to their parents before getting baptized. But they appeared to be happy, and when I asked if it was what they had really wanted, they said it was. They seemed awed by the integrity, devotion, and love they’d seen exhibited by the others on the retreat.

On the train, as Sarah and Cecilia slept, Veronica crept into my sleeping bunk.

“I didn’t agree with everything Philip taught,” she confided in me.

“Really? Like what?” I asked.

“He taught us that if we follow Jesus, everything will work out in our lives,” Veronica answered. “That we will be successful in what we try, that whatever we ask for in the name of Jesus we will receive, and we won’t have suffering.”

I didn’t speak, wanting her to continue. She did.

Dangerous Territory

Dangerous Territory