- Home

- Amy Peterson

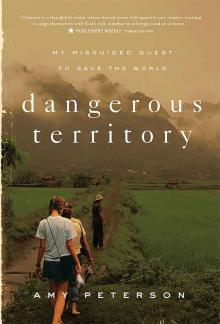

Dangerous Territory Page 4

Dangerous Territory Read online

Page 4

Twenty-eight girls and five boys turned to each other, and the room filled with voices. I paced up and down the aisles between desks, listening in. They blushed and paused when I came close, then kept talking, wide-eyed and gesturing with busy hands.

At this school undergrads were formed into cohorts by year and major—these groups would take all their classes together for four years. My third-years were comfortable with each other and had the benefit of a year with a foreign English teacher before I showed up, so they weren’t confused by my strange ways—requiring them to do their own homework instead of copying others, for example, or asking them to be silent rather than chattering while I taught, or basing their grades on weekly assignments rather than on one test at the end of the semester.

Teaching—a career I had never once considered while studying English literature in college—turned out to be a delight. I found that I adored poring over books in our small teaching library, exploring lesson plans online (when our dial-up internet connection allowed), and using those resources to come up with my own curriculum. But the icing on the cake was the students, who were up for anything from mock debates to acting out a simple English version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which they did with costumes of their own design, melodramatic swords, and near kisses.

It took me about a month of teaching before I realized I wasn’t living like a backpacker anymore. I’d moved my clothes from the backpack to the dresser, placed pictures on my desk, and bought a new scarlet bedspread. I had become that close cousin of the backpacker, the expat, making my life in a foreign place as one perpetually outside the local culture. As much as Lisa and I tried to live like locals—shopping in the open air market, eating street food at sidewalk cafés, slurping noodles for breakfast, buying rice-flavored ice cream bars from small men pushing freezers on wheels—our skin tone made blending in impossible. Going to the market was exhausting when all the sellers wanted to touch us, hardly believing we could be real.

Sometimes we’d ride motorbike taxis over to the small, air-conditioned grocery store on the other side of town, where only foreigners and the very rich shopped, just for a break from being the center of attention. It remained impossible to find bacon or shrink-wrapped meat of any kind, but we took what we could get. Lisa bought breakfast cereal and non-refrigerated, “shelf-stable” milk (there was no fresh milk in town), and I bought a block of cheese from Australia. We relaxed at the cash register, paying the sticker price for the food. That allowed us to avoid the mental stress of bargaining—should I try to pay the same amount as the locals? Should I be willing to pay a higher “foreigner” price since I do, after all, have more resources? Which will make me most acceptable to the locals?

We might have lived more like expats if we had the choice, but there was hardly any expat community in this war-torn province—no way to indulge our longing for our home culture in foreign restaurants, no English bookstores, no Dunkin’ Donuts or KFC like we’d found in Bangkok. When we tired of the constant attention our skin color earned us, or at night when it wasn’t totally safe for us to go out alone, we would retreat to our apartments, eating scrambled eggs and fried potatoes and watching The West Wing on DVD.

Lisa and I had been told there were no other Americans in our poor farming town, but there were just a few other expats. One night we met them for dinner at the Lotus Restaurant, on the lake at the edge of town. We were there to be polite, I think, more than to make friends. I went out of curiosity, too. I knew why I’d moved to this country, but why had they?

In the large, empty room, we gathered around three tables loosely pushed together. We were sweating despite the night breeze through the open windows. Outside the sky was already black, and the hotel lights and street lights were reflecting on the surface of the lake.

The Frenchwoman wanted a revolution. “I do not say that we can change anything,” she said dramatically, her voice tinged with a French accent. She was dark-skinned, short and plump, with large lips and black eyes. “But we cannot just sit by and say nothing when injustice is occurring!” Violette, in her fifties and luxuriously dogmatic, had just told a story about her top student, who had been told she needed to pay a bribe to begin work on her master’s degree; after she paid the bribe, she was still denied admission.

Ann, a red-headed Canadian in her twenties, backed Violette. Her words were just barely slurred by her second light beer. “Yeah, I mean, I’m not saying we are going to start a revolution among the people or anything,” she began. “God, that’s not what we’re here for. I’m not even saying in twenty years anything will have changed. But we have to start by at least talking about it. Acknowledging that corruption exists.”

Violette taught French at the university where Lisa and I worked, and Ann was a Fulbright Scholar. The others at the table, all men, were in town for a short time to provide farming and irrigation systems training.

The Canadian next to Violette, a man with immense black eyebrows, finally got his chance to jump in. “But the problem is systemic,” he argued. “You’re never going to change anything from the bottom up in a corrupt system. You’ve got to change the whole system. You’ve got to begin at the top.” His father was a politician in Canada and Ann told me later that she thought he was full of himself, that he talked to the rest of us as if we were children.

Violette unconsciously drew her silk scarf from around her neck to around her shoulders, alternately tugging each end. “Yes, but why will the politicians change anything? They do not need to. They already live in the four-story houses and drive the expensive cars. The système works for them.”

Violette and the Canadian Eyebrows went at it for another six rounds, each making points that rarely had any real reference to each other. The waif-skinny sunburned German man nodded off at the table, and the Finnish man seemed exuberant just to be part of an English conversation.

As the youngest in the group, by quite a bit, I sat listening, admiring Violette’s passion, aware of my own uncertainty. Lisa didn’t say much either. The discussion introduced us to a common expat dilemma: How could we respect another culture while also desiring to rid it of injustice? I didn’t have any answers. I hadn’t come to this place thinking of Systems or Injustice: I had come thinking only of individuals and Jesus. But I’d started to see that the needs of the people I came to serve might be more complex than I had realized—and to wonder if my role as a teacher made me complicit in the university system’s corruption.

I wondered if our expat dinner, this odd grouping on a lonely lake, this international discussion broken every half hour by the sound of a train rushing by, meant anything. We were the few foreigners living in the Middle of Nowhere, Asia, the World. Though we were in what was known as the most revolutionary province in our country, it seemed to hold little promise for changing the world anytime soon.

Despite our talk, we seemed to hold little promise for changing the world anytime soon either.

By the fourth round of beers—theirs, not mine, since Lisa and I were observing our organization’s policy against drinking—the political clash of ideas really began. I felt I was being drawn into the scene of a Hemingway novel, with our city an unfortunate 2003 replacement for Paris, the expats trying to make sense of life in the corner of a dark café. There’s a similar kind of despair and loneliness and passion in the air, though little of the glamour of the French capital.

We were the strangers in town, I thought to myself as we dispersed on bicycles, in a car, on a motorbike. We were the ones who, for many unknown reasons, had given up life in western countries to live in this small rural town—but did we even know enough of this culture to begin to think of changing it? I was sure, as I pedaled away, that the top-down, change-the-system approach espoused by the Canadian had merit, as did the idealistic, fight-oppression-and-injustice (liberté, egalité, fraternité) approach championed by the French woman. But I wondered about our motivations. I had gone to this p

lace wanting to do something grand too, but now I wondered if I understood what that meant. Have we even learned enough about this country to earn the right to want to change things? Should I focus solely on teaching English, evangelism, and discipleship, or could I work for systemic justice as well?

We were all full of ourselves at dinner, bandying about our theories as if we had within ourselves the power to do great things. Maybe we did have an influence to wield within the university, a privilege we could leverage on behalf of our poor students. We should do that, and we should work to make unjust systems just. Yet we were still foreigners, with no guarantee that we could affect this culture from our outsiders’ position. And even if we could make changes, wouldn’t some of the corruption remain?

After all, corruption is not just bound to a system; it is intrinsic to the human heart. The best hope for change comes from people who understand both kinds of corruption—and who recognize the corruption in our own prideful hearts as well.

4

Do Not Easily Leave

It is a prolonged system of picnicking, excellent for the health, and agreeable to those who are not over-fastidious about trifles, and who delight in being in the open air.

David Livingstone, describing arduous travel in the uncharted interior of Africa

Of course it costs life. It is not an expedition of ease nor a picnic excursion to which we are called. It is going to cost many a life, and not lives only, but prayers and tears and blood.

Samuel Zwemer, the “Apostle to Islam”

On my twenty-first birthday, I was alone in France. Well, not entirely alone: I was staying at Taizé, an ecumenical monastic community, along with hundreds of other pilgrims. But none of them knew it was my birthday, of course. Near five o’clock, I made my way to the counter of the open-air café that sold snacks every afternoon. I ordered a single plastic cup of red wine and toasted myself, twenty-one, alone and free.

Then David, a new friend I’d made at Taizé, joined me. “Hey,” he said, plopping his gangly, green-eyed, curly-haired self on the bench next to me. I liked him. “How was your day?” he asked. “You didn’t come to the Bible study.”

Every day at Taizé began with communal prayer in the candlelit chapel. Swaths of reddish orange fabric hung from ceiling to floor, like tongues of fire descending, and I meditated, open-eyed, as I learned the chants we’d sing in Latin, French, Spanish, English, and Italian.

After morning prayer, each of us received a baguette with butter, a cup of coffee, and a square of dark chocolate (which to this day is my ideal breakfast). Each newcomer was assigned a community responsibility, and mine was dishes: after the meal I joined a group of teenage Irish boys in the kitchen to clean up. Later we had midday prayer, lunch, optional workshops and group Bible studies led by monks, time for silence and contemplation, supper, and evening prayer. I’d skipped the optional Bible study that day.

“I spent the afternoon by the lake, in silence,” I told David. “Well, I wanted it to be silence—there were some construction trucks on the other side of the lake. Kind of drove me crazy.” I paused, wanting to keep talking with him. “So, how did you find out about Taizé?” I asked.

“The University of Virginia gave me a fellowship to study the spirituality of monastic communities in Europe,” he said, “So I’ve been traveling around. What about you?”

I felt a little out of my league. “I just finished a semester in Italy,” I said. “When classes ended, I backpacked with some friends for a while. They’re all stateside now, so I’m here by myself for a week before I head home.”

Silence drew out awkwardly. I watched people ordering snacks at the counter, and listened to the birds singing around us. “I love backpacking,” I said finally. “And I love being here—it’s so different from the kind of spirituality I grew up with. But I can’t imagine making a monastic kind of commitment—agreeing to stay in one place forever.”

I wondered if David was Catholic. If he wanted to be a monk.

“Do you know how Taizé started?” he asked. I shook my head.

“Brother Roger started Taizé in 1940, while France was in the middle of World War II,” David said. “He came from Switzerland. His idea was to make a place where people who were wounded or hopeless could find work and peace. Soon men came from around the world to join. It’s one of the only monastic communities that has monks who are Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox.”

“He was kind of like a missionary,” I mused. The not-too-distant bells rang, calling us to prayer.

These men left their homes to join Taizé—but then they stayed. The power of their venture was only realized through a commitment to planting roots.

That night I dug out a sheaf of papers I’d been carrying around Europe with me—a bunch of sermons that preached verse by verse through Hebrews 11. I thought that was the perfect chapter to study while backpacking, because it commended heroes of faith who “acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth,” who were “seeking a homeland”—and not the one they’d left.

That was my favorite metaphor for the Christian life, because I never really felt at home where I was, either. If I were a “sojourner,” then I could be free to float along, unconcerned about fitting in, without becoming overly invested, safe from the complications of relationships. I always got twitchy when I stayed still too long: I took weekend road trips, bought last minute plane tickets. I changed the subject any time Charley tried to get serious about settling down.

David and I wandered down to the chapel. I thought about asking him for his e-mail address, or asking him to send me a copy of his research paper when he finished it, but I was too scared. I never saw him again.

* * *

Sometimes I recalled my conversation with David at Taizé while I worked on grad school assignments in the evenings in Asia. For one paper, I was supposed to research a missionary or a missionary movement. I chose the desert fathers and mothers, the very first Christians who retreated from their world to find a purer spirituality. Eventually they formed communities together, communities like Taizé, committed to a place. Later, some of those communities sent missionaries out to new places.

One of the books I was reading was The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward. It’s a paperback with glowing golden icons on the cover, Jesus and a monk with long faces and halos. I was highlighting it at my desk one afternoon when I heard footsteps in the hallway outside. I opened the door.

“Come in!” Four girls from one of my classes entered shyly. Minnie was holding a tiny kitten. “Miss Amy, I think you are lonely,” she began. “You said you like a cat.”

“Yes, I would like a cat. You brought me a cat? This is so sweet!” I held the tiny striped animal close to my chest. It mewed fiercely, its whole body thumping with fear.

“Please, sit down and have some tea,” I urged the girls.

“We can’t stay,” they answered.

“Oh, really?” I asked. “Well—” I paused. I didn’t know enough about the culture yet to realize that the girls wouldn’t accept my invitation to tea unless I repeated it several times. “What should I feed the cat?”

They looked at each other, conferring with language I couldn’t comprehend.

“Maybe some fish,” they said.

“Okay.” This would be a challenge.

“Bye, teacher, see you tomorrow,” they said, heading down the stairs.

After they left, I set the kitten on the floor. She leapt away from me, hiding herself under my bed. I couldn’t reach her, and she just kept mewing. She was probably too young to leave her mother. And now I needed to figure out how to buy the right kind of fish for her. Feeling overwhelmed, I decided to wait until Lisa returned from her class. She’d help me figure it all out. In the meantime, I returned to my book.

The first and most famous of the desert fathers, St. Anthony, w

as once asked, “What must one do in order to please God?” His answer had three parts:

“Whoever you may be, always have God before your eyes; whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy Scriptures; in whatever place you live, do not easily leave it.”

As I read about these monks who stayed quietly in the same places, doing the same tasks and praying the same prayers for years and years, I began to wonder if my own definition of sojourner was missing something. Had I misunderstood this metaphor? Or worse, had I been using a false idea to excuse my own wanderlust, my desire for independence, and my fear of commitment?

When Peter wrote to the elect resident aliens scattered throughout the Roman provinces of Asia Minor, he was writing to Christians facing persecution: his description of them as sojourners and exiles, whether literal or metaphorical, was intended to help them understand how to live with patience and holiness as an oppressed minority in the empire. It was a reminder that Christians ought to live with “reverent fear” wherever we are, aware that our truest identity is as citizens of a different Kingdom.

But I’d been using the title sojourner to justify my rootlessness. I wasn’t persecuted or oppressed. I hadn’t been forced into exile. I was simply exercising my privilege and freedom to leave my home, safe with a passport to bring me back when I was ready. I was at the top, not the bottom, of the day’s empire economies. To claim that metaphor for my own was to discredit the very real persecution that originally undergirded it.

Here’s the thing I began to realize about my wanderlust, as I listened to the bewildered cries of my displaced kitten: I was not an exile. I was not a mythic hero out to conquer a new frontier, finding freedom in the wild blue yonder. To put it plainly, I was discovering that restlessness is not always a virtue. For anyone to have a meaningful presence in the world, at some point the desire to go must transform into a desire to stay.

Dangerous Territory

Dangerous Territory